Python variables - behind the scenes¶

We will now examine how Python stores objects in memory, and the link between variables and memory location. You might be wondering why you need to worry about this, but it is actually essential to understand this in order to make best use of Python's capabilities and avoid mistakes/bugs.

Assignment and modification¶

Consider the following two examples. First:

a = 2

b = a

print(a, b)

a = 4

print(a, b)

This should hopefully make sense so far.

Now consider the following example:

a = [2, 3, 4]

b = a

a.append(5)

print(a, b)

In this case, modifying a modified b too! This is not as intutitive... But if we do:

a = 9

print(a, b)

This time, changing a did not change b - what is happening?

The key is to understand that doing:

variable = something

will change which object variable is pointing to in memory (assignment). On the other hand, when calling a method with:

variable.method()

some (but not all) methods will modify the variable in-place (more information below).

Let's go over the examples above but this time with a graphical representation, where the yellow circles show the variables, and the blue rectangles show the objects in memory. If we do:

a = 2

b = a

a = 4

then what is happening is the following.

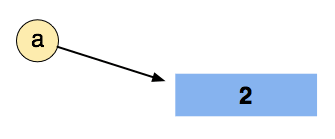

First, when doing a = 2 we create space in memory for the value 2 and we assign that location in memory to the variable a:

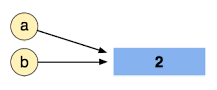

By doing b = a, we are now assigning the variable b to point at the same object as a:

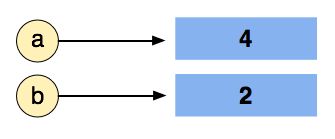

And finally by doing a = 4 we re-assign a to point at a different place in memory (containing 4) but b still points at the same object (2):

Now if we follow the same logic for the second example:

a = [2, 3, 4]

b = a

a.append(5)

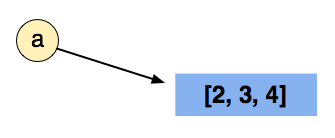

we again start off by creating space in memory for the list [2, 3, 4], then we point the variable a to that location.

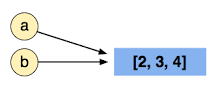

By doing b = a, we then point b to the same location as a, so the list exists only once in memory (this is very important):

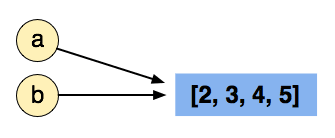

We now modify, in-place, the object that a is pointing to with a.append(5) - the concept of modifying the object is very important - we are not creating a new list, it is still in the same place in memory, even if it has one extra element now:

This means that since b is pointing to the same place in memory, it will also see a list with (now) four elements!

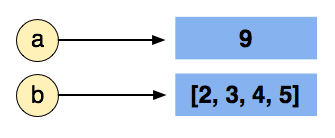

Then, if one does a = 9, then one is not modifying the list, but instead assigning a to point to a region in memory with the value 9:

In order to talk about this behavior, we use the terms copying and referencing. When we do:

variable = something

then the value is actually created when writing something. The assignment merely creates a pointer (“reference” is just a fancy name for that) from a name to that value, and you could have more such names pointing to the same something.

Another important point is that what is on the right hand side will get evaluated first, and will (conceptually) result in the creation of a new object unless the something is a reference already (in which case variable and something will just refer to the same value. In the following cases, something is a “literal” (i.e., the representation of a value in the source code), and a new value will be created:

a = 2

b = a + 1

c = b * 2

print(a, b, c)

In the second assignment in the following, something is a reference, and hence no new object is being created:

a = [2,3,4]

b = a # b points to the same object than a

Python's built-in id() function will tell you the identity of its argument:

id(a), id(b), id(c)

Copying¶

In some cases, the behavior described above is not desirable, and we want to make a true copy, not just a reference, because we want to change b without changing a:

from copy import deepcopy

a = [2,3,4]

b = deepcopy(a)

a.append(5)

print(a, b)

id(a),id(b)

The copy module contains a function copy, too. If you want to really understand what's going on, it will probably help to create a nested list (as in [range(2), range(3)]), copy that and manipulate the inner lists.

Note that slicing (usually) creates a copy, too (but be careful with numpy arrays), which is why in quite a bit of source code you see slices when a copy is desired:

a = range(4)

b = a[:]

id(a),id(b)

Methods¶

As mentioned above, some methods modify object in-place:

a = [1,2,3]

a.append(5) # modifies ``a``

and some will return a copy rather than modifying the object.

s = 'hello'

s2=s.upper() # returns a copy of the string in uppercase without modifying s

id(s),id(s2)

It should be clear from the documentation (e.g. s.upper?) how a particular method behaves.

Mutable vs immutable objects¶

Some objects are immutable, which means that they cannot be modified - examples include float, int, str. For instance, when doing:

a = 1.

print (id(a))

a = 2.

print (id(a))

In the second line, a new location in memory is created for 2., and a points at that object, not at 1. (in other words, the float is not being changed, it is a that is pointing to a different object).

On the other hand, list, dict, and Numpy arrays are mutable, which means the object can be modified:

a = [1,2,3]

a.append(5)

After the second line, a still points at the same list, but the list has now been modified.

Functions¶

A final but important point is that when passing variables to functions, variables are passed as references, so:

def do(x):

x.append(1)

a = [1,2]

do(a)

print(a)

The following, however, just changes the value x in do references and thus has no effect outside of do:

def do(x):

x = 0 # re-assigns x to 0, but only in the function

a = [1,2]

do(a)

print(a)

Copying and Referencing Numpy arrays¶

With Numpy arrays, one has to be particularly careful with the copying/referencing distinction. With a few exceptions (and superficially contrary to the behaviour of almost all other python objects), most slicing/masking operations in Numpy indicate references, not copies, to the data:

import numpy as np

x = np.arange(10)

y = x

y[3] = 1

x

This is similar to lists, but now consider the following:

x = np.arange(10)

y = x[::2]

y[3] = 1

x

Even though we took a slice with a given start, end, and slice, the resulting array was still just a reference, or view, of the array in the original array! (note that for lists, x[::2] returns a copy!). This can be very handy when combined with masking:

x = np.arange(10)

x[x < 5] = 0.

x

There is one exception to the referencing, which is:

x = np.arange(10)

y = x[[1,3,2,2]] # returns a new array, not a view

y[0] = 9

x

As before, you can explore this further to understand in what cases references or copies are made. However, be aware that using id() on a view will be different from the original array, even though the view is actually pointing to a subset of the original array.

In the case of Numpy arrays, one can force a copy by doing:

x = np.arange(10)

y = x.copy()

y[0] = -1

x

y

Before you start cursing the numpy authors because it might seem they were out to confuse you: They did this because very common operations become very fast in this way, and in practice that's much less of a trap than you may suspect.

Exercise¶

The following questions are just to test your understanding of the variable assignment - you don't need to write any code - just try and think of what the output will be, then you can try it out to check if you got it right:

What will a be after the following?

a = [1, 3., [1, 2, 3], 'hello']

b = a[0]

b = 4.

What will c be after the following?

c = [1, 3., [1, 2, 3], 'hello']

d = c[2]

d.append(8)

What will e be after the following?

e = [1, 3., [1, 2, 3], 'hello']

f = e[2]

f = [1, 2]

What will g be after the following?

g = [1, 2, 3, 4]

h = g[::2]

h[0] = 9

What will i be after the following?

import numpy as np

i = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4])

j = i[::2]

j[0] = 9# You can try it here.