There are two alternative ways of further simplification. One is the

orbit average, which uses that any distribution function, being a

steady state solution of the collisionless Boltzmann equation, can be

expressed as a function of the constants of motion of an individual

particle (Jeans' theorem). For the sake of simplicity, it is assumed

that all orbits in the system are regular, as it is the case for

example in a spherically symmetric potential; thus the distribution

function ![]() now only depends on maximally three independent integrals

of motion (strong Jeans' theorem). Let us transform the Fokker-Planck

equation to a new set of variables, which comprise the constants of

motion instead of the velocities

now only depends on maximally three independent integrals

of motion (strong Jeans' theorem). Let us transform the Fokker-Planck

equation to a new set of variables, which comprise the constants of

motion instead of the velocities ![]() . Since in a spherically

symmetric system the distribution only depends on energy and the

modulus of the angular momentum vector

. Since in a spherically

symmetric system the distribution only depends on energy and the

modulus of the angular momentum vector ![]() , the number of independent

coordinates in this example can be reduced from six to two, and all

terms in the transformed equation (8) containing derivatives to other

variables than

, the number of independent

coordinates in this example can be reduced from six to two, and all

terms in the transformed equation (8) containing derivatives to other

variables than ![]() and

and ![]() vanish (in particular those containing

derivatives to the spatial coordinates

vanish (in particular those containing

derivatives to the spatial coordinates ![]() ). Integrating the

remaining parts of the Fokker-Planck equation over the spatial

coordinates is called orbit averaging, because in our present example

(a spherical system) it would be an integration over accessible

coordinate space for given

). Integrating the

remaining parts of the Fokker-Planck equation over the spatial

coordinates is called orbit averaging, because in our present example

(a spherical system) it would be an integration over accessible

coordinate space for given ![]() and

and ![]() (which is a spherical shell

between

(which is a spherical shell

between

![]() and

and

![]() , the minimum and

maximum radius for stars with energy

, the minimum and

maximum radius for stars with energy ![]() and angular momentum

and angular momentum ![]() ).

Such volume integration is, since

).

Such volume integration is, since ![]() does not depend any more on

does not depend any more on

![]() carried over to the diffusion coefficients

carried over to the diffusion coefficients ![]() , which become

orbit-averaged diffusion coefficients.

, which become

orbit-averaged diffusion coefficients.

Orbit-averaged Fokker-Planck models treat very well the diffusion of orbits according to the changes of their constants of motion, taking into account the potential and the orbital structure of the system in a self-consistent way. However, they are not free of any problems or approximations. They require checks and tests, for example by comparisons with other methods, like the one described in the following.

We treat relaxation like the addition of a big non-correlated number

of two-body encounters. Close encounters are rare and thus we admit

that each encounter produces a very small deflection angle. Thence,

relaxation can be regarded as a diffusion process ![[*]](./footnote.png) .

.

A typical two-body encounter in a large stellar system takes place in

a volume whose linear dimensions are small compared to other typical

radii of the system (total system dimension, or scaling radii of

changes in density or velocity dispersion). Consequently, it is

assumed that an encounter only changes the velocity, not the position

of a particle. Thenceforth, encounters do not produce any changes

![]() , so all related terms in the Fokker-Planck equation

vanish. However, the local approximation goes even further and assumes

that the entire cumulative effect of all encounters on a test particle

can approximately be calculated as if the particle were surrounded by

a very big homogeneous system with the local distribution function

(density, velocity dispersions) everywhere. We are left with a

Fokker-Planck equation containing only derivatives with respect to the

velocity variables, but still depending on the spatial coordinates (a

local Fokker-Planck equation).

, so all related terms in the Fokker-Planck equation

vanish. However, the local approximation goes even further and assumes

that the entire cumulative effect of all encounters on a test particle

can approximately be calculated as if the particle were surrounded by

a very big homogeneous system with the local distribution function

(density, velocity dispersions) everywhere. We are left with a

Fokker-Planck equation containing only derivatives with respect to the

velocity variables, but still depending on the spatial coordinates (a

local Fokker-Planck equation).

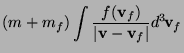

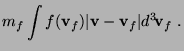

In practical astrophysical applications, the diffusion coefficients

occurring in the Fokker-Planck equation are not directly calculated,

containing the probability ![]() for a velocity change

for a velocity change

![]() from an initial velocity

from an initial velocity ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() , and

, and

![]() are of the dimension velocity

(change) per time unit, and squared velocity (change) per time unit,

respectively, one calculates such velocity changes in a more direct

way, considering a test star moving in a homogeneous sea of field

stars. Let the test star have a velocity

are of the dimension velocity

(change) per time unit, and squared velocity (change) per time unit,

respectively, one calculates such velocity changes in a more direct

way, considering a test star moving in a homogeneous sea of field

stars. Let the test star have a velocity ![]() and consider an

encounter with a field star of velocity

and consider an

encounter with a field star of velocity ![]() . The result of the

encounter (i.e. velocity changes

. The result of the

encounter (i.e. velocity changes ![]() of the test star) is

completely determined by the impact parameter

of the test star) is

completely determined by the impact parameter ![]() and the relative

velocity at infinity

and the relative

velocity at infinity

![]() ;

thus by an integration of the type

;

thus by an integration of the type

| (10) |

| (11) |

|

|||

|

(12) |

|

|||

|

(13) |

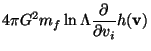

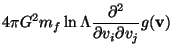

![\begin{displaymath}

\bigg(\frac{\delta f}{\delta t}

\bigg)_{\rm enc}= -4\pi G^2...

...

{\partial^2 g \over\partial v_i\partial v_j}

\Bigr)\Biggr]

\end{displaymath}](img93.png) |

(14) |

Before going ahead the question is raised, why such approximation

can be reasonable, regarding the long-range gravitational force,

and the impossibility to shield gravitational forces as in the

case of Coulomb forces in a plasma by opposite charges. The key is

that logarithmic intervals in impact parameter ![]() contribute equally

to the mean square velocity change of a test particle,

provided

contribute equally

to the mean square velocity change of a test particle,

provided ![]() (see e.g. Spitzer87, chapter 2.1). Imagine that

on one hand side the lower limit of impact parameters (

(see e.g. Spitzer87, chapter 2.1). Imagine that

on one hand side the lower limit of impact parameters (![]() , the

, the

![]() deflection angle impact parameter) is small compared to

the mean interparticle distance

deflection angle impact parameter) is small compared to

the mean interparticle distance ![]() . Let on the other hand side

. Let on the other hand side

![]() be a typical radius connected with a change in density or

velocity dispersions (e.g. the scale height in a disc of a galaxy),

and

be a typical radius connected with a change in density or

velocity dispersions (e.g. the scale height in a disc of a galaxy),

and ![]() be the maximum total dimension of the system. Just to

be specific let us assume

be the maximum total dimension of the system. Just to

be specific let us assume ![]() , and

, and ![]() . In that case

the volume of the spherical shell with radius between

. In that case

the volume of the spherical shell with radius between ![]() and

and ![]() is

is ![]() times larger than the volume of the shell defined by

the radii

times larger than the volume of the shell defined by

the radii ![]() and

and ![]() . Nevertheless the contribution of both shells

to diffusion coefficients or the relaxation time is approximately

equal. This is a heuristic illustration why the local approximation

is not so bad; the reason is with other words that there are a lot

more encounters with particles in the outer, larger shell, but the

effect is exactly compensated by the larger deflection angle for

encounters happening with particles from the inner shell.

If we are in the core or in the plane of a galactic disc the density

would fall off further out, so the actual error will be smaller than

outlined in the above example. By the same reasoning one can

see, however, that the local approximation for a particle in a

low-density region, which suffers from relaxation by a nearby

density concentration, is prone to failure.

. Nevertheless the contribution of both shells

to diffusion coefficients or the relaxation time is approximately

equal. This is a heuristic illustration why the local approximation

is not so bad; the reason is with other words that there are a lot

more encounters with particles in the outer, larger shell, but the

effect is exactly compensated by the larger deflection angle for

encounters happening with particles from the inner shell.

If we are in the core or in the plane of a galactic disc the density

would fall off further out, so the actual error will be smaller than

outlined in the above example. By the same reasoning one can

see, however, that the local approximation for a particle in a

low-density region, which suffers from relaxation by a nearby

density concentration, is prone to failure.

These rough handy examples should illustrate that under certain conditions the local approximation is not a priori bad. On the other hand, it is obvious from our above arguments, that if we are interested in relaxation effects on particles in a low-density environment, whose orbit occasionally passes distant, high-density regions, the local approximation could be completely wrong. One might think here for example of stars on radially elongated orbits in the halo of globular clusters or of stars, globular clusters, or other objects as massive black holes, on spherical orbits in the galactic halo, passing the galactic disc. In these situations an orbit-averaged treatment seems much more appropriate.